Frenchtown: Where the gumbo was hot and the accents were thick

Frenchtown Origins

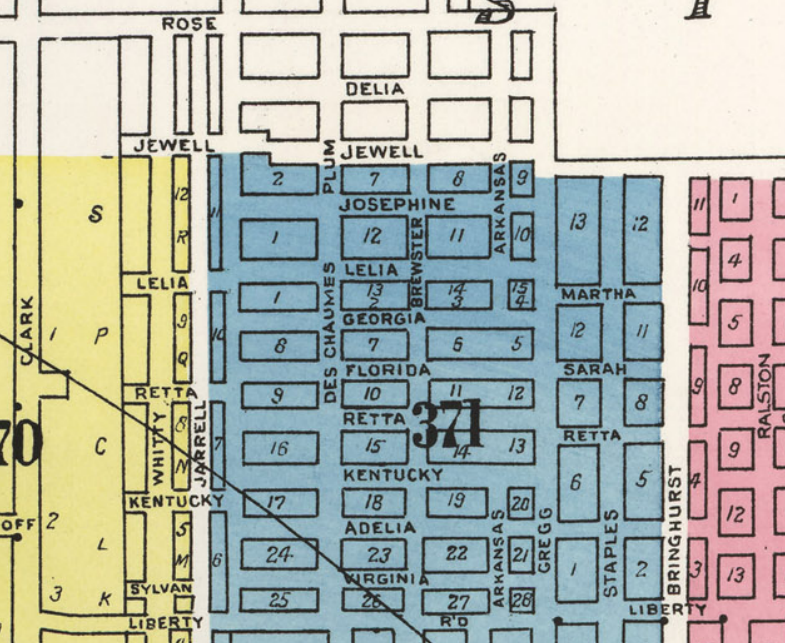

On November 7, 1947, Sigman Byrd took his readers on a stroll to Frenchtown, a Creole-French neighborhood to the northwest of Houston’s 5th Ward. Like the name entails, this lively neighborhood was founded by “colored” Louisianians, also known as Creoles, whose bloodline contained an African, Spanish, and French admixture. Roughly a decade after World War I, the first wave of Creoles came looking for work near Houston as the railroad opportunities were better than the cotton and fruit picking they were used to. The second wave, roughly 5 years later, was due to the Mississippi Flood of 1927 which displaced many Creoles from their homes. For many of the displaced Louisiana residents, Frenchtown, the newly established community of Creoles in Houston, was the perfect place to rebuild their lives.

For its first few decades, Frenchtown was rich with the culture, traditions, and history of its Louisiana Creole inhabitants. Family was the center of the community, and everyone pitched in and kept an eye out for each other. “Donner le main,” which translates into “to hold hands” was the Frenchtown way of doing things. It was not uncommon for neighbors to watch the children of another family, or for the entire community to come together and build a home for someone else. Even leisurely activities and get-togethers were always community-centric. Festivals playing lively music now referred to as zydeco and house-parties called “la-la’s” were Frenchtown’s way of having fun.

Many of Frenchtown’s older residents spoke French or Creole Patois and didn’t speak or understand English very well. They built their own school, church, and stores for the community, and were for all intents and purposes, and self-contained Creole village in the midst of a growing Houston. In 1947, Byrd estimated that the population of Frenchtown was somewhere between 3,000 and 10,000 residents.

While the older generation continued the traditions and customs of their home state, the younger generations began to assimilate into Texan culture, much to the dismay of the older residents. It is this topic that Sigman Byrd was discussing with Frenchtown matriarch, Laura Dupree, in her grocery store @ 3010 Jewell (Jewel) Street.

Laura Dupree

Laura was 67 at the time of Sigman Byrd’s article, and spoke with him inside of her grocery store, Dupree Grocery. According to Laura, in the almost 3 decades of Frenchtown’s existence, she was seeing fewer Creole customs taking place. Her take? The new generation wanted to “be Texas” instead of Creole. To back up her argument, she told Sigman that fewer and fewer homes were being built in the traditional “donner le main” fashion, and that she had begun seeing paid carpenters building homes in the community.

It’s at this moment that Laura’s daughter, Annie Laurie, chimed in that her mother was wrong, and her recently purchased home was proof. She and her husband, Claude Norwood, bought their home @ 3018 Jewell (Jewel) a year before Byrd’s article, and stated that the community helped them clean and prepare the home. Claude agrees and tells Byrd, “And now I’m studying French” as a testament to the cultural traditions that were still going strong in the community.

Immediately after this conversation, Byrd states that a jukebox in the Creole Nightclub across the street began to blast “The Port Arthur Waltz” by the legendary Cajun fiddler, Harry Choates. Upon hearing the song Laura Dupree covered her ears and yelled to Byrd, “This is what I mean.” Sigman then comments that the Creole Nightclub was run by a Creole couple, John and Lilli Robey, who were apparently one of the first Creole families in the area.

I’m unsure if Laura was fed up due to the fact that the Texan-titled song was made by a Cajun who moved to Texas, or the fact that Creole family was blasting the debauchery. Whatever the reason, Laura wasn’t happy.

Frenchtown Establishments

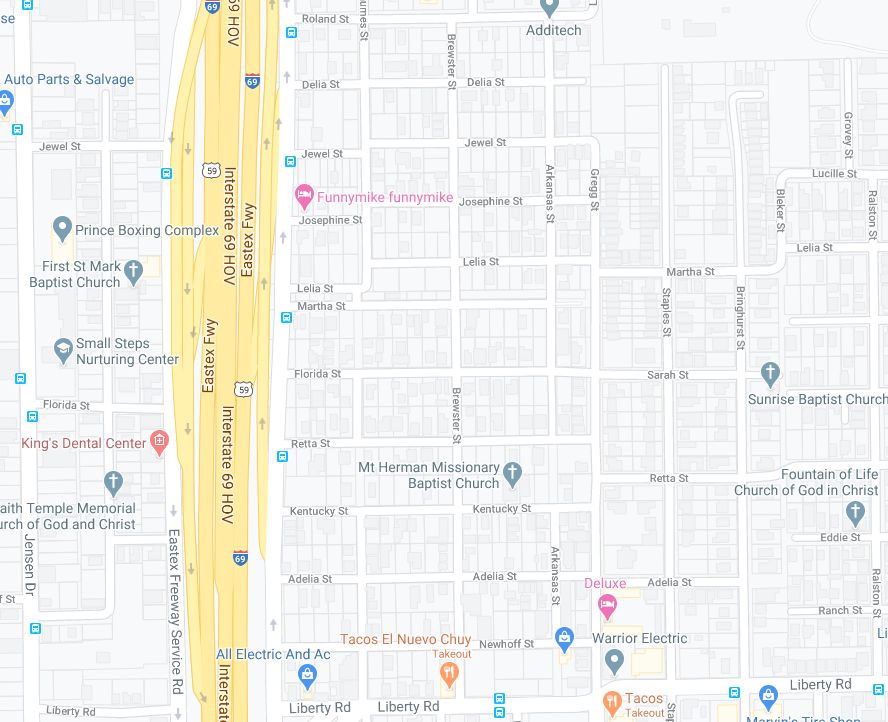

The late 1950’s and early 1960’s brought destruction to the once thriving community. The construction of Highway 59 rid Frenchtown of two streets, Whitty and Jarrell, along with many homes and businesses. Additionally, the 60’s brought integration, which meant businesses and neighborhoods that originally did not allow Black people were now forced to do so. This caused a severe decline in profits for the Frenchtown and Fifth Ward businesses that had thrived for decades. It also meant that the younger generation of Frenchtown could move to new neighborhoods and explore areas of Houston that they originally were barred from.

Laura Dupree’s grocery store, Dupree Grocery, was built in 1939 and located at 3010 Jewell (Jewel) Street. Due to the construction of Highway 59, Dupree Grocery met the same demise as many other businesses in the area.

The 1946 home of Laura’s daughter, Annie Laurie, and her husband, Claude @ 3018 Jewell (Jewel) Street is also gone. For reference, the wooden home directly to the left of the lot below is 3020 Jewel Street.

The Creole Nightclub mentioned in the article was located at 3101 Jarrell Street and also no longer exists. Two Frenchtown streets, Jarrell and Whitty, would have been precisely where Highway 59 and its feeder roads are located now.

Another Frenchtown establishment that is long gone is Chevalier Grocery. Sigman described the grocery store, run by Armand and Mary Rose Chevalier, as the “social center for Frenchtown.” Byrd asked the owners their opinion on Louisiana traditions, and whether or not they were dying out, and Armand Chevalier had an interesting response.

Armand Chevalier, owner of Chevalier Grocery

“…But we are a Breaux Bridge people. We have Creole blood. We stay in the store and mind our own business. If the Lafayette and Opelousas people want to live like the Texas Negroes, that’s their business.”

Chevalier Grocery, once the social center of Frenchtown, is just an empty lot now. What was left of Chevalier Grocery appears to have caught on fire sometime between 2010 and 2011. The above Street View is from May 2011, and the building has since been demolished.

Hope for Frenchtown

Laura Dupree died July 4, 1957 from uterine cancer at the age of 76, and with her death, and the deaths of the other patriarchs and matriarchs of Frenchtown, the history began to die with them. There have been efforts to revitalize the community and preserve the history that is left, such as the now defunct Frenchtown Community Association, which disbanded after the death of its leader. Many of the organizers of the Frenchtown Community Association, are, however, working with other leaders in the Frenchtown community to preserve the history and renovate abandoned homes in the area.